What happens to the deaf child when he or she leaves the environment and protection of school? Is the care given by pre-school, primary and special school experts entirely in vain, if young people emerging into an adult world can find no scope for talents they might have? If there is anything odd about some of these youngsters, it is only that they have not enjoyed a faculty that the more fortunate take for granted. In this article the women’s department gives a parent’s point of view with that of Miss Kay Deare, whose speciality is the deaf child.

The deaf child is sometimes, in comparison, with other disabled children, a forgotten part of society.

In the district which Miss Kay Deare, the Advisor for Deaf Children, covers, there are approximately 100 deaf children on file.

The boundaries of Miss Deare’s area are Mokau, Tokoroa, Waihi, and Port Waikato. This year she has seen over 1000 children with hearing defects.

“Deafness is caused by many things. Rubella or German measles, until recently was a main one. English measles and meningitis are some of the more common causes. The cause of the deafness of one third of deaf people is unknown” said Miss Deare.

There are 10 advisory services for the deaf in New Zealand. They test children from the age of nine months, and fit them at that stage with hearing aids. As soon as it is felt the child is able to understand, he is taught to lip-read.

SPEECH AIDS

“If children don’t start developing language at an early age, it becomes increasingly hard. We get them making sounds on the speech trainers,” said Miss Deare.

“Proving the children with hearing aids and speech trainers is, in actual fact, providing them with sound. Through these aids the deaf are no longer as isolated from the hearing world,” she continued.

“The aids do not give them perfect hearing but merely amplify the sounds for them. This includes amplification of background noises, such as cars passing, and things being dropped, and it does not lend itself to concentration.”

School-age children, perhaps, face the most trying time of their life when they start in a normal school. As with all deaf people, the two major problems, understanding and being understood, now being more important.

There are three schools for the deaf in New Zealand. They are Kelson in Auckland, Sumner in Christchurch and St Dominic’s in Feilding.

Today, however, the trend seems to be towards the children living at home and attending units in ordinary schools.

DEAF UNITS

“If the children are away at school, they are treated like visitors when they come home. They know little of home life and find communication very hard,” said Miss Deare.

“In Hamilton there are four deaf units, three at Hamilton West and one at Melville Intermediate. Next year there is going to be a deaf unit at Melville High School.”

According to Miss Deare teachers of the deaf must have their primary school teacher’s certificate, plus a year’s special training in Christchurch.

She herself, became interested in the deaf when she had a deaf pupil in one of her classes in Taranaki. She became so absorbed with the problems that face the deaf, and the people they come in contact with, she decided to specialise.

“It is easy for us to relate one word to another, because we have heard words used in different ways, but the deaf child takes everything literally,” Miss Deare said.

WORD SENSE

“I was teaching a class the word ‘step’ including doorstep, step ladder, step back, step forward and so on.

“Then I told a boy from the class to ‘step over the book’. He couldn’t relate the words to one another. He went and picked up the book, held it above his head, and went and stood on a step.

“The pupils know the meaning of the word by itself, but when it is teamed up with others they get confused. What the deaf child doesn’t know, is what you haven’t taught him,” Miss Deare explained.

“Deafness, I believe, is the most misunderstood handicap of all, and its about time people with preconceived ideas forgot themselves, rolled up their sleeves and got stuck into really putting the work of putting the deaf on the map.” So said the resigning Social Welfare Officer to the Deaf in Auckland, Mr Trevor Fear.

Hamilton parents agree with him. The mother of two profoundly deaf teenagers, said most people are sympathetic towards the deaf but rarely go out of their way to help them.

“The stage from school to job presented the biggest problem for me,” she said. “I found it more difficult to find employment for my younger daughter than my elder one.

“I realise that the girls have not reached an equal academic standard to some people of their own age, but they do have the ability to learn, if someone has the patience to show them how.

“Eventually they were offered employment in a local office. It is all right for people to say they could get a job, but don’t forget they are human too, and it is no use taking on a job that you are not happy in.”

Mrs May Baker who is in charge of the recording staff of the Auckland Herd Improvement Association office where the two girls are employed, had these comments to make.

“I feel it is a great pity that the elder of the girls is deaf as I feel she would have been brilliant had she had normal hearing.

“She is already doing the work that some of the senior girls are doing. It is now done by punch cards, but if the old system was still in use I am confident she would have picked it up with no trouble.

“She uses the photocopying machine and the people who tested her for this thought she was excellent.

“The younger of the girls is very keen to learn. She has great ability to absorb information. We have booklets about the work that all the girls are doing and she takes them home and reads them. Most of what she reads she retains.

“I would definitely encourage employers to give these young people a chance. In my case it has been most rewarding.”

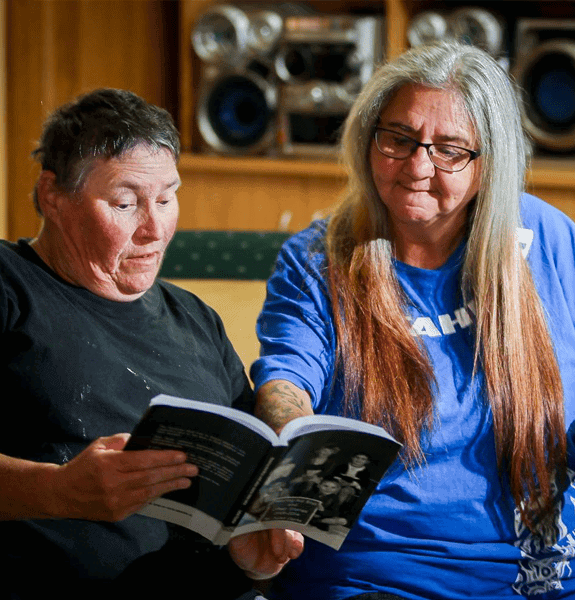

Photo caption: Mr Robert Allen, the teacher of the deaf, at Melville Intermediate, explains where the photo he is holding was taken and what it represents, to an attentive Robert Wilson.